RAPIDS Network Inpatient Prospective Payment Systems (IPPS) Proposed Rule Response

RAPIDS (Regulation And Policy for Infectious Disease Stewardship) Network:

Inpatient Prospective Payment Systems (IPPS) Proposed Rule Response

The following organizations have participated in the creation or review of this policy brief: Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), Federation of American Hospitals (FAH), Cepheid, Rubrum Advising

The comment below was submitted on June 10, 2025, as a response to the 2026 Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment Systems Proposed Rule.

Introduction

We are writing to comment on the 2026 Hospital Inpatient Prospective Systems (IPPS) Proposed Rule on behalf of the RAPIDS (Regulation And Policy for Infectious Disease Stewardship) Network Interoperability Working Group. Our multi-stakeholder approach united experts from hospital organizations, hospital systems, infectious disease professional organizations, electronic health record vendors, and diagnostic manufacturers. Participants include Cepheid Diagnostics, Rubrum Advising, and AAMC.

The RAPIDS Network believes that increased interoperability can strike the balance between the important need for reporting public health data to Federal, State, and local officials and the administrative burden that falls on health systems to do so. As such, the group supports CMS’ proposed actions to promote interoperability through use of digital quality measurement, creation of the optional bonus measure for TEFCA participation, transition of the Medicare Promoting Interoperability attestation measures to performance-based reporting, and interest in improving the quality and completeness of data exchanged between hospitals. While these proposed actions propel the country a step closer to true interoperability, it will first require modernization of public and private data infrastructures.

Medicare Promoting Interoperability Program Objectives and Measures Moving TowardPerformance-Based Reporting

Current infectious disease quality measures associated with antimicrobial resistance (AMR) are largely focused on surveillance, tracking the rates of prioritized infections, antimicrobial use, and antimicrobial resistance in hospitals. While this information is relevant, these measures often do not drive meaningful change in the quality-of-care that patients with infections receive. We propose the development of new performance-based quality measures that catalyze improvement in antimicrobial stewardship efforts.

As a group, we are interested in measuring patient outcomes rather than adherence to specific processes that may not be feasible for all hospitals and may not always correlate with improved outcomes. Performance-based reporting facilitated by interoperable data transfer can help hospitals address critical gaps in understanding. First, the impact of AMR on healthcare resilience and reliability could be quantified. Secondly, the effectiveness of the variety of initiatives to improve antibiotic use and infection prevention and control could be determined. For example, the impact of diagnostic excellence on antimicrobial stewardship practices based on antibiotic prescription data could substantiate test-to-treat models, which is consistent with the current administration’s efforts to make American healthy again. Third, analyzing patient- and provider-level antibiotic usage across healthcare settings could allow for better stratification and risk adjustment towards targeted intervention and/or designing a QAPI program as part of the CMS “Infection Prevention and Control and Antibiotic Stewardship Program Condition of Participation”.

The data modernization efforts at the CDC, including the Data Modernization Initiative (DMI) and Public Health Data Strategy (PDHS), are critical to reducing AMR. While the PDHS lays out

important strategic steps, DMI serves as the vehicle for innovation and improvement in data collection. Since 2019, some progress has been made to accelerate modernization through federal policies, data standards, and system interoperability. CDC modernization efforts must continue to be prioritized in tandem with quality measure restructuring to lower administrative and hospital burden. These efforts will allow for the development of report cards for hospitals to benchmark progress against national averages, driving improved care.

ImprovementsintheQualityandCompletenessoftheHealthInformationEligibleHospitalsand CAHs are Exchanging Across Systems

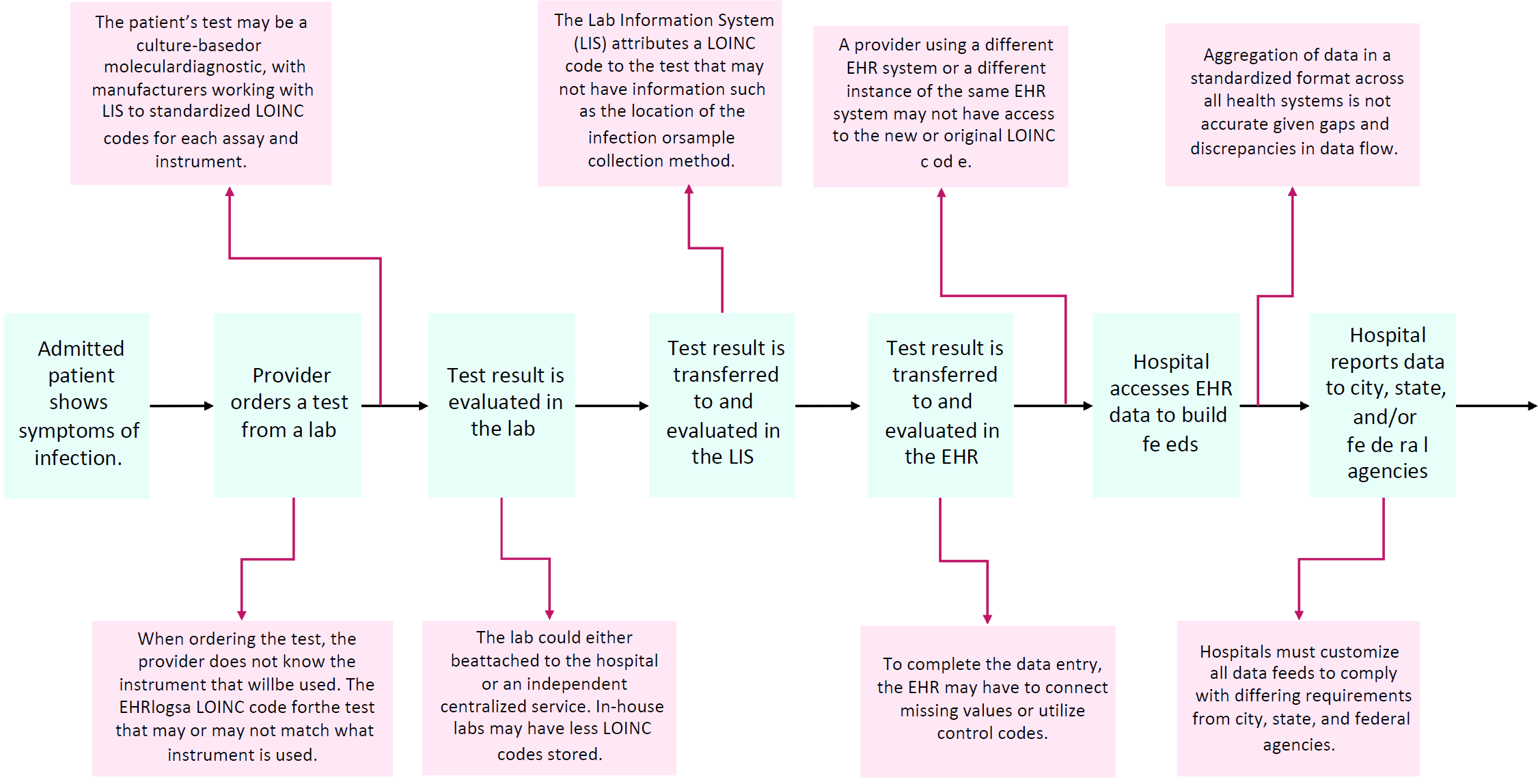

While the Interoperability Working Group supports the transition to health information exchange through entities such as TEFCA and streamlined DQMs that standardize data elements required for quality measure reporting, we believe that data modernization must be prioritized in parallel. We have identified a number of unaddressed barriers to achieving complete and accurate data transfer in the infectious disease space (see Figure 1). Primarily, the lack of alignment between data standards disrupts the flow of laboratory data, leading to the delivery of incomplete information to not only public health agencies, but also the patients and the clinicians caring for them.

The process begins when a provider orders a laboratory diagnostic test. The order is placed in an electronic health record (EHR), which assigns a Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes, or LOINC codes based upon the chosen diagnostic test. The test result is recorded in the Laboratory Information System (LIS), which includes fields such as the assay name and specific instrument. In attributing a LOINC code to the diagnostic test that was performed, the inconsistency in data elements used by the LIS and EHR could result in data gaps, such as inaccurate identification of the location of the infection, resistance profile, sample collection method, testing modality (including sensitivity and specificity). When the test result is transferred to the EHR, inconsistent data elements can lead to missing values and utilization of unspecific control codes. For example, many reports are scanned into the EHR rather than accurately captured in distinct data fields. These interoperability issues during data transfer create significant uncertainty in using the aggregated EHR data for public health reporting.

To improve the quality, completeness, and accuracy of data reporting towards driving quality improvement in hospitals, diagnostics, LIS, EHRs, and hospitals must utilize consistent data standards for effective data exchange. The Interoperability Working Group advocates for national guidance to be developed by the Office of the National Coordinator/Assistant Secretary for Technology Policy (ONC/ASTP). The guidance should codify data standards for all vendors that would allow for seamless and streamlined data transfer towards digital quality measurement that can enable advanced capabilities such as real-time public health reporting and point-of-care clinical decision support.

Currently, the United States Core Data for Interoperability Plus (USCDI+) specifies some of the foundational data elements necessary for measurement based on EHR data. We believe that a similar core set of standardized data requirements should be developed for LIS and diagnostic outputs that are tailored to their use cases while aligned with quality measure data requirements. ASTP/ONC should additionally create a LOINC reference database for all diagnostic tests, standardizing their use among diagnostic manufacturers, LIS, and EHRs. We support continued collaboration among CMS and all relevant stakeholders towards standardizing the individual data elements used to build quality measure specifications and calculate the measure logic from the diagnostic machine output to all data reporting channels.

Once national guidelines are in place, it will be critical to promote their adoption so that all relevant stakeholders can plan to upgrade their Health IT systems before CMS transitions to true digital quality measurement. We support CMS’ existing mechanism for promoting adoption of national health IT guidelines, which involves 1) mandating health systems to use Certified Electronic

Health Record Technology (CEHRT) in order to receive payment through the CMS Promoting Interoperability Program and Merit-based Incentive Payment System; and 2) requiring EHR vendors that seek CEHRT qualification to meet the criteria set by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information and Technology (ONC), including compliance with USCDI. We believe that ONC/ASTP should develop a new version of CDI that includes all required data elements for public health reporting, which Health IT systems should comply with to obtain CEHRT.

While CMS’ CEHRT mandate effectively encourages EHR vendors to incorporate all required data elements per USCDI+, no such incentivization exists for LIS and diagnostic manufacturers to promote compliance with national standards. Without such an incentive, the cost and burden of upgrading Health IT systems to enable data standardization may not be tenable for many low resource hospitals, in-hospital laboratories, and independent LIS vendors. These facilities require resources and funding to update their technologies and processes to facilitate FHIR-based reporting. We further believe that any certification-based incentive that is developed for LIS and diagnostic manufacturers should not mandate use of all CDI+ data elements, but rather a limited set of relevant fields that would facilitate data transfer.

Prioritizing data modernization can not only improve data quality but also lessen burdens for both the federal administration and health systems in the service of helping Americans remain healthy by providing timely insights into hospital and community acquired infections.

Request for Information on the Transition Toward Digital Quality Measurement in CMSQuality Reporting Programs

The Interoperability Working Group supports transitioning to digital quality measurement using Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) as the data standard. However, many private and public infrastructures are currently ill-equipped to make this shift since interoperability has historically been encouraged and incentivized, without enforced regulation. Therefore, the adoption of data modernization guidance should be prioritized ahead of requiring FHIR in system- wide regulation, given that a premature transition could disrupt critical data reporting pathways.

While digital quality measurement would ultimately relieve substantial burden from both health systems and public health agencies, the burden of enabling this transition to accommodate the requisite data standards falls on the private sector. The Interoperability Working Group emphasizes that the hundreds of vendors responsible for each step of the data transfer process—from the diagnostic machines to laboratory information systems (LIS) to electronic health records (EHR) and finally to public health agencies—must coordinate updates to their infrastructure so as to preserve the accuracy and completeness of the data. This is best achieved through large-scale adoption of national guidelines and standards as previously outlined.

The Interoperability Working Group supports the objective of CMS’ DQM initiative to adopt self- contained measure specifications and code packages that can be transmitted electronically via interoperable systems. Though DQM may be helpful for some quality measures to better assess public health and outcomes data, transitioning to DQM for all measures may not warrant the risk and burden. Given that DQMs require additional considerations for compliance due to the specificity of information, we request the creation of regulatory frameworks to protect patient safety and privacy. In choosing which quality measures to move to DQM, CMS should formally evaluate the potential difference in performance and benefit that could be achieved and weigh it against the security risk and cost. If the impact of conversion to DQM does not outweigh the burden for a given quality measure, we believe that conversion to FHIR-eCQMs may be sufficient. During the conversion from QRDA to FHIR, we underscore the importance of data validation to mitigate data gaps and inconsistencies, given that the outputs using QRDA and FHIR can differ even when using the same quality measure definition. We also advocate for flexibility in allowing health

systems to choose whether or not to use the FHIR server for data extraction and calculations during this transition period.

Proposal to Add an Optional Bonus Measure Under the Public Health and Clinical DataExchangeObjectiveforData Exchangeto Occur with a Public Health Agency (PHA) usingthe Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA), Beginning with theEHR Reporting Period in CY 2026

The Interoperability Working Group supports the proposal for an optional bonus measure under the Public Health and Clinical Data Exchange. We agree that TEFCA participation would allow physicians to access more complete patient information through the data-sharing framework and may be incentivized with an optional bonus measure. This ability to collate different data sources on a patient-level can also improve the comprehensiveness of surveillance initiatives. This functionality could benefit quality measurement that is designed to capture 1) patient-level healthcare utilization across the continuum of care, including post-acute settings; and/or 2) performance data related to interoperability, financial savings, and patient quality of care. This could unlock advanced capabilities such as real-time public health reporting and surveillance, and point-of-care clinical decision support.

Use of TEFCA presents many opportunities that come at a cost. The required data standard for TEFCA is HL7 CDA, which is less flexible and more difficult to integrate with modern technology than other standards like FHIR. While TEFCA currently supports FHIR and is beginning to require the data standard in stages, many hospitals and laboratories may not yet support FHIR or HL7 CDA. Data standardization is a costly venture, requiring more than financial resources. Staffing and technical constraints, as well as system compatibility and EHR upgrades, pose barriers for many hospitals, such as critical access hospitals and those not part of health systems. These obstacles can hamper mass participation in TEFCA through QHINs. We therefore support incentives for the use of TEFCA (the bonus measure) but believe TEFCA should continue to evolve over time to reflect advances in data flow while reducing potential burden and cost.

Rubrum Advising

Rubrum Advising